Brief Introductions To Religious Texts will serve to educate the general public on the great religious texts, what they are and basic scholarship related to them. The Philosophy of this series is to educate with the hope of clearing up misconceptions and fighting ignorance, which can lead to hate. Also to make this information available and easily Understandable by the general public. Interaction with the blog, asking questions, and sharing are greatly encouraged. Words appearing in bold are important terms defined at the end of the post. Also included at the end of the post are online resources for further study.

Any one whom has ever read a modern Protestant Bible, such as the King James Version or the New International version and has read a Bible such as the Douay Rheims or the New Revised Standard version has probably realized that in these Bibles are extra books not found in most Protestant Bibles. These books are vastly unknown to many, but not all Jews and Protestants. What exactly is this deuterocanonical literature? It is a set of books or parts of books there are not included in the Judaic canon of the Hebrew Scriptures, yet are found in the Septuagint and in some Christian versions of the Hebrew Biblei.

What’s In a Name?

There are some issues in the world of religion in which you can tell where a person or group stands by the names they use, and this is the case of the deuterocanonical literature. Both Catholic and Orthodoxii Christians accept this literature as canonical. To Orthodox Christians it is known as the anagignoskomena and to Catholics it is known as the deuterocanon, where as Protestants, who mostly reject them, call it the apocrypha. Anagignoskomena is a Greek word that literally means those which are to be read or ecclesiastical books. Deuterocanon is a combination of two Greek words deuteros (second) and kanon (rule or measuring stick). The term means these texts were recognized as canonical at a later date, to differentiate them from the “protocanonical” texts. The protocanonical books are the books of the TaNaK, all of which are universally accepted by Christiansiii. The word apocrypha is Greek as well, and means concealed or hidden. The way the word is used today it has the connotation of “set aside” or “withdrawn” from full canonical status as Scripture.iv Occasionally these texts are called inter-testamental literature. This is because when the initiator of the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther included these in his Bible, he placed them in a separate section between the Old and New Testaments.

The term apocrypha is problematic for many reasons and is the source of much confusion. The collection of non-canonical books outside of the New Testament are also known as apocrypha, this causes the two distinct groups of books to be mistaken for one another. The term apocrypha is also very subjective, it means different things to different groups. To a Catholic the term is applied to the Pseudepigrapha, a collection of Jewish texts different from those of the deuterocanonical literature, that have been preserved and utilized by different groups of Christians but, “with some exceptions (in Ethiopia, for example), not included in the

Bible.”v The term is viewed by some Catholic and Orthodox Christians as offensive. The words deuterocanonical and apocrypha, while referring to the same books, are not synonyms.vi Of the names for these books, deuterocanonical literature is the least problematic and is the preferred name by Scholars. The Style Manual for the Society of Biblical Literature suggests that the name deuterocanonical literature be used in place of apocrypha for academic writingvii.

The Books Of The Deuterocanonical Literature

The texts of the deuterocanonical Literature belong to several different genres, occasionally the same book will contain multiple genres. “These include wisdom literature, which gives advice for right conduct and a successful life, linked to a religious outlook; apocalyptic writing, offering hope of momentous supernatural intervention at the end of history in order to save the people of God, sometimes through the agency of an anointed one or ‘Messiah’; historiography or writing that purports to be history; edifying stories which are essentially folk-tales with a religious message; rewritten Bible, where a familiar story from Scripture is retold with different emphases; prayers and psalms which may have had a liturgical or devotional function.”viii

The Following Books are accepted by both Catholic and Orthodox Christians:

1 Esdras

2 Esdras

Tobit

Judith

The Rest of the Book of Esther

The Wisdom of Solomon

Ecclesiasticus (Also known as Book of the All-Virtuous Wisdom of Joshua ben Sira (Jesus Ben Sirach), The Book of Ecclesiasticus, Siracides, or just simply Sirach)

Baruch

The Letter of Jeremiah

The Additions to the Book of Daniel:

The Song of the Three Children (with the

Prayer of Azariah)

Susanna

Bel and the Dragon

The Prayer of Manasseh

I Maccabees

II Maccabees

The following books are accepted by Orthodox churches, either as fully canonical or as appendices:

III Maccabees

IV Maccabeesix

Psalm 151

History Of The Deuterocanonical literature

The deuterocanonical literature originated during the time of the second temple period, with some created in the Jewish homeland, while others were created abroad. This literature did not originate with the Septuagint, but their history and development are intertwined. The Septuagint was initiated in the late third century BCE. As I noted in last week’s post, the Septuagint began as just a translation of the Torah, the first five books of Moses, but gradually grew to include the whole Hebrew Bible. However as Alexandrian Jews worked, they began to include books authored closer to their own period of time, and some books continued to be authored and added for sometime afterward. The books that would come to be known as the deuterocanon are mixed in with the protocanonical books in the Septuagint, and in this Alexandrian Jewish collection of books, there was no distinction made between the two. It is important to keep in mind that at this point in time the Jewish canon was not closedx. The Torah was defined and the prophets were as well, but the writings were not. Some books which are not apart of the Writings today, where accepted by some Jews at this time, such as the Book Of Enoch, while others which are apart of the writings today, such as Esther were not accepted by some Jewsxi. It is important to note too that the Septuagint became the first Bible for Christians.

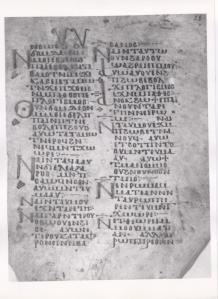

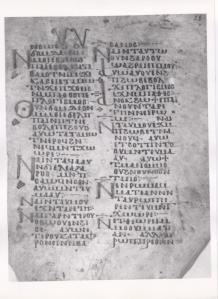

Codex Vaticanus, one of the oldest copies of the Septuagint and the Bible.

After 70 CE the Rabbis in Palestine, acknowledged a twenty-four book Palestinian canon,what is known today as the Jewish Scriptures or Hebrew Bible. This is due to their belief that revelation began with Moses and ended with Ezra. The deuterocanonical literature came later than Ezra, and some were written in Greek. This denied them acceptance as Scripture. The Rabbis did debate books after 70 CE, but these were books that were accepted into the Judaic canonxii, not the deuterocanonical books. The Talmud is full of warnings against these books. Rabbis of the Talmud “claim that the person who brings together more than twenty-four books creates confusion.”xiii and “one who reads in the outside books will have no place in the world to come.”xiv Though it is important to note that for sometime after this, Rabbis continued to study and quote from Ecclesiasticus.xv

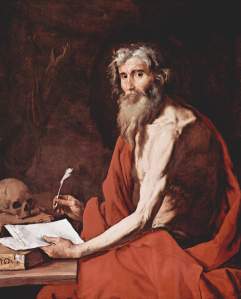

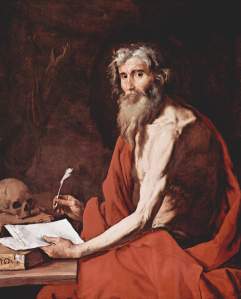

Jerome painted by Jusepe de Ribera

Early Christians tended to make no distinction between the books of the Septuagint and tended to quote from them all. As history progressed some of the eastern Christian thinkers gained knowledge of the contents of the Judaic canon of scripture. These thinkers wanted to limit their canon to the twenty-four books accepted by Jews. In the fourth century when Jerome was commissioned to compile the Latin Vulgate, he went to Bethlehem to learn Hebrew, so he could translate straight from the Hebrew text. While there he discovered that the number of books in the Hebrew canon was not the same as that of the Septuagint. While most of the books of the Septuagintxvi were included in the Latin Vulgate, Jerome made a distinction between the books of the Jewish scriptures and those found only in the Septuagint.xvii

I said in last weeks post that Jerome’s distinction between the protocanonical and deuterocanonicalxviii books would have far reaching consequences for the Old Testament of the Protestants. Western Christians were aware of the distinction made by Jerome and this distinction would be one of the leading problems Protestants had with this literature. This was by no means the only issue they had with it. During the heated Protestant reformation, the deuterocanonical literature became embroiled in the debate. Some saw it as a source for Catholic doctrines, such as being able to obtain salvation by works. Some passages such as Tobit 12:9 supported this,

“For almsgiving saves from death and purges away every sin. Those who give alms will enjoy a full life,”xix

One common slogan among Luther and other Protestant reformers was Sola fide, a Latin phrase meaning, by Faith alone. This refers to the Protestant belief that salvation comes from faith alone and not works. Because of these doctrinal conflicts and the distinction made by Jerome Protestants did not accept these books as canonicalxx. Though initially they still retained this literature in there Bibles. Originally the texts were separated from the other books of the Old Testament and placed into a section of their own. Later generations of Protestants would expunge these books from their Bibles all together. In the 1800 and early 1900’s many Protestant Bible Societies outright refused to print any Bible with the deuterocanonical literature. This changed in the mid 1900’s, and now one can find these texts in many Bibles, not just in Catholic or Orthodox Bibles, but in Ecumenical Bibles, such as the Revised Standard Version and The New Revised Standard Version.

The Significance Of The Deuterocanonical Literature

These books of immense value, furnish us with an extraordinary amount of details about Judaic thought and practice in the centuries before the advent of both Christianity and Rabbinic Judaismxxi. These books are being studied more and more at a scholarly level due to what they disclose about the religious ideas of their authors and the communities which originally accepted themxxii. The deuterocanonical literature especially, are priceless testaments to the numerous varieties of the Jewish religion during the time of the Second Temple. This is about the segment of time which falls in between the composition of the TaNaK and the New Testament booksxxiii.

These books tell us about grave military, religious, and political persecutions and oppressions, despite this these texts also contain profoundly soul-stirring calls to encouragement and reassurance. These texts tell us of the trials that not only the people went through, but that of which their culture did as well, due to the encounter with Hellenistic culture, both in Palestine and the diaspora. They tell narratives of heroes of the Jewish faith, both fierce combatants and peaceful people who died for their faith. It is these narratives which offer us an unfathomed awareness of a sacred tradition and a race fighting to endure the challenges of the different ancient nations that dominated themxxiv. These texts provide ample testament to the continued role in Judaic culture, of the narrative. The books of the deuterocanon also indicate the continued advancement of the wisdom tradition and the increase in the functions of females in the sacred texts. In this literature women are depicted as the innocent vindicated, as with Susanna and Sarah in the book of Tobit, as the heroic mother, who died for her faith in 4 Maccabees, as Wisdom embodied as a female in the Wisdom of Solomon 6-12 and Ecclesiasticus 24, or as with Judith, a freedom giving agent of the Jewish people, sent by God.xxv Finally this content illuminates the texts of the New Testament as their authors make many allusions to the deuterocanonical literature.

A Manuscript of IV Maccabees.

Religious Views Of The Deuterocanonical Literature Today

Below are short summaries of views of religious groups and points which were not discussed above.

1. Jewish

Most modern Jews do not accept the deuterocanonical literature. However some reports claim that Beta Israel, the Jews of Ethiopia do, accepting books that are not found any where else. It is worth noting that while the majority of Jews do not accept these books, two of these books, I Maccabees and II Maccabees relate the story of Hanukkah, the only Jewish religious holiday not to be mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.xxvi

2. Oriental Orthodox

All Oriental Orthodox Christians accept this literature, though to varying degrees. The Coptic Orthodox Church accepts the same books that are accepted by Catholicsxxvii, Where as the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Armenian Apostolic Churchxxviii accepts III Maccabees. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church accepts most of this literature, but rejects the books of Maccabees, while adding unique books not included by any other Church.xxix

3. Eastern Orthodox

Although this literature is included in the canon of the Church, its authoritative status compared to that of the undisputed books, is still an unanswered question. Orthodox Christians, imitating Athanasius, refer to the protocanonical literature as “canonical” and to the deuterocanonical literature as anagignoskomenaxxx.

4. Protestant

Some Protestants, such as the The Anglican Churchxxxi accepts them for instruction of the Church, but not to base doctrine on. In Bibles, which are Anglican, you will find these books in a separate section either between the Old and New Testaments or after the New Testament.

Important Terms Related To The Deuterocanonical Literature

Anagignoskomena: The term for the deuterocanonical literature used by Eastern Orthodox Christians. It is a Greek word that means those which are to be read or ecclesiastical books.

Apocrypha: The term for the deuterocanonical literature historically used by Protestants. It is a Greek word that means concealed or hidden.

Athanasius: Athanasius of Alexandria, also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor or, primarily in the Coptic Orthodox Church, Athanasius the Apostolic, was the twentieth bishop of Alexandria.

Beta Israel: A people of uncertain origin, living since ancient times in what is now central Ethiopia and practicing a form of Judaism. During the period 1984-1991 most Ethiopian Jews were resettled in Israel.xxxii

Deuterocanonical literature: A set of books or parts of books there are not included in the Judaic canon of the Hebrew Scriptures, yet are found in the Septuagint and in some Christian versions of the Hebrew Bible. This is the preferred, scholarly name for this literature.

Diaspora: The settling of scattered colonies of Jews outside Palestine after the Babylonian exile.xxxiii

Hanukkah: A Jewish festival, lasting eight days from the 25th day of Kislev (in December) and commemorating the rededication of the Temple in 165 BCE by the Maccabees after its desecration by the Syrians. It is marked by the successive kindling of eight lights.

Martin Luther: The first Protestant Reformer and the founder of the Lutheran Church.

Protestant reformation: Also known as the Protestant Revolution or simply the Reformation, was the schism within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other early Protestants.

Protocanonical: The books of the TaNaK, all of which are universally accepted by Christians.

Society of Biblical Literature: The Society of Biblical Literature, founded in 1880 as the “Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis,” is a constituent society of the American Council of Learned Societies, with the stated mission to “Foster Biblical Scholarship”

Sola fide: A Latin phrase meaning, by Faith alone. This refers to the Protestant belief that salvation comes from faith alone and not works.

Online Resources

Websites

Septuagint

The Septuagint Online

http://www.kalvesmaki.com/LXX

Bibles With The Deuterocanonical Literature

King James Version

http://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Apocrypha-Books/

New Revised Stand Version

http://bible.oremus.org/

Douay-Rhiems

http://www.biblestudytools.com/rhe/

The Deuterocanonical Literature

A Great Website for these texts and others from the same time period, as well as scholarship on these works.

http://www.earlyjewishwritings.com/

PDFs

The Septuagint

A New English Translation of the Septuagint Translated By Pietersma & Wright

https://mega.co.nz/#!C89VBaLa!Gv3aCd2xbrF70Di1H2YRBwNBSbpcA7zjYbvoOw5noH8

Bibles That Contain The Deuterocanonical Literature

King James with The Apocrypha

http://www.davince.com/download/kjvbiblea.pdf

The New Revised Standard Version

http://www.allsaintstupelo.com/Bible_NRSV.pdf

The Eastern or Greek Orthodox Bible Or The Holy Bible Of The Orthodox Church Old Testament

https://mega.co.nz/#!ilNngDra!hSH8YTzWwO8PGSnKK1hpVeLYeZ0Si0XL7BWxQJWNUP0

Douay-Rheims Bible of 1914

Catholic Bible

http://www.catholicspiritualdirection.org/douayrheimsbible.pdf

The Beloved and I

The same books accepted by Catholics

The Beloved and I Volume 4 Ezra to Job To Translated By Thomas McElwain

https://mega.co.nz/#!ugsRFA4Z!tnWbLIxFl5WknoIbY3mb_bXEa0MKX1mI3Cnxw6ALut0

The Beloved and I Volume 5 Psalms To Sirach Translated By Thomas McElwain

https://mega.co.nz/#!j9FizbpA!LNG60aEUyirwT063rvYX14g2fThadWgJQyOhTu2yDBQ

The Beloved and I Volume 6 Isaiah to Malachi Translated By Thomas McElwain

https://mega.co.nz/#!Ts1gxKoL!Dgnf8uBoePjpu16Jrmlkmqu6ZOW5DeYnv4jcjhyhi0w

Scholarly Collections Of Deuterocanonical Literature

The Apocrypha And Psuedepigrapha Volume One Apocrypha Edited By R. H. Charles

https://ia700303.us.archive.org/14/items/apocryphapseudep01charuoft/apocryphapseudep01charuoft.pdf

The Apocrypha And Psuedepigrapha Volume Two Psuedipigrapha By R. H. Charles

Contains IV Maccabees

https://mega.co.nz/#!z8EWjL7Z!xGdeZkYgL11xvYLLNpDBRPPqmSynB_bXMJKakHAFPt0

The Encyclopedia Of Lost and Rejected Scriptures By Lumpkin

Includes the deuterocanonical texts and other non-canonical books.

https://mega.co.nz/#!25lAHYIB!zTng9-KnW71h9W9mClCK0UaqU40YKif_Q3xe4bpL7l4

The Five Books Of Maccabees Translated By Henry Cotton

Includes a Fifth book, that is not apart of the deuterocanonical literature

https://mega.co.nz/#!Ttt1xCZT!Lr7RDrqfKR-zAYQxGU5-IPhp1KxWHEe6S8ZY4ui5WgI

Scholarly Works On The Deuterocanonical Literature

The Lost Books Of The Bible For Dummies

https://mega.co.nz/#!Kg0ihRwb!t8RDl4nEBNuTm1XOV-tcgcP5Tc5GP48hg_6O0wuuYmM

Oxford Handbook of Biblical studies

Its focus is on broad Biblical scholarship, but there is a section dedicated to this literature.

https://mega.co.nz/#!epl3kSKb!P01NzH72xt17XNSUQ7EXqjC6NTMI2RFA-06Ip0P1zsY

Scholarly Works On The Septuagint

The Septuagint By Dines

https://mega.co.nz/#!C49FXTYa!a8AcpNZlhHlqLsmizoK_K81NmZfFvsfmkAtRD0uNpcE

The Septuagint In Context

https://mega.co.nz/#!a98HVZbK!HE_FOB6RHGJAGZDqw3sywgylk-xX1wPb3QH1qAD-8LY

Translation and Survival

https://mega.co.nz/#!XkkknDCI!rSi0TrbxdfJLMHwX0JDXkyKI4wNbNbFME9Qd9TBa10k

God willing, next week’s post will be on The Pseudepigrapha

iAchtemeier, Paul J. The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary. New York, New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996. , pp 47 39-40

iiBoth Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox accept these books, though not all of these books are accepted by all Oriental Orthodox Churches. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church omits the Books of Maccabees, for example.

iiiHaper Collins Bible dictionary, pp 40

ivHaper collins Bible Dictionary, pp 39-40

vHaper collins Bible Dictionary, pp 40

viLumpkin, Joseph B. The Encyclopedia of Lost and Rejected Scriptures: The Pseudepigrapha and Apocrypha. Blountsville, AL: Fifth Estate, 2010. Print.

vii Alexander, Patrick H. The SBL Handbook of Style: For Ancient Near Eastern, Biblical, and Early Christian Studies. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1999. Print, pp 17

viii Rogerson, J. W., and Judith Lieu. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print., pp 491

ixThe Greek and Slavonic Orthodox Churches accept it as an appendix, but the Georgian Orthodox Church accepts it as canonical.

xSmith-Christopher, Daniel L., and Stephen J. Spignesi. Lost Books of the Bible for Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Pub., 2008. Print, pp 64

xiThe Essenes, whom are believed by most scholars to be the authors of the Dead Sea Scrolls, seem to have accepted the book of Enoch, either as canonical or at least useful to be read. They did not have a copy of Esther, though scholars are unsure why, as every other book of the TaNaK was found.

xvHaper collins Bible Dictionary, pp 40

xviIII and IV Maccabees and Psalm 151 were not included

xviiHaper collins Bible Dictionary, pp 41

xviiiThese terms did not exist in Jerome’s time.

xxLuther also felt similarly about the New Testament Epistle of James, but finally decided to accept it as canonical.

xxi Lost Books Of The Bible For Dummies, pp 80

xxii The same is also true of the Pseudepigrapha, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the writings of Josephus and Philo, all of which I will address in coming posts.

xxiii Oxford hand book of biblical studies, pp 491

xxivLost Books Of The Bible For Dummies, pp 80

xxv Harper Collins Bible dictionary, pp 42

xxvi Though it is the most well attested Jewish religious holiday in ancient documents, as not only is it mentioned in I and II Maccabees it is also mentioned in the Talmud and in the writings of Josephus.

xxvii III Maccabees is found in some manuscripts but is not considered canonical.

xxviiiIV Maccabees was also accept earlier in the tradition, but is no longer considered canonical.

xxix Such as The Book of Enoch or Jubilees, these will be discussed in more depth in mext weeks post.

xxx The Eastern/Greek Orthodox Bible, 9

xxxi Also known as the Church of England and as the Episcopalian Church in the U.S.